← Head back to the Starter Manager Guide

Delegation is a huge part of management. Many people believe that management consists of ‘telling people what to do’. This isn't wrong: as we've seen earlier, the manager's job is to increase the output of the team; ‘telling people what to do’ is an important way of achieving that. But that's not all there is, and it can be done very badly.

One of the most surprising things to me when I first started teaching management was how often new managers meddled in tasks they had already delegated out. This happened even when they knew not to do so! It was, in fact, as if they couldn’t help themselves.

They felt distraught. “I know I shouldn’t have redone her work” one said, “But she was so slow!”

After a bit of time, I realised that new managers — especially those in a startup — used to be good individual contributors first. They became senior people in the company as the business grew, and became managers by accident: that is to say, they were gradually given responsibility for the output of others.

If you find yourself in this situation, you’re probably very good at what you do. Individual contributors who are effective tend to dislike giving up tasks they are good at, for one of two reasons:

- They are impatient when they see a subordinate execute a task that they’re good at — either because of speed, or of quality.

- They are emotionally invested in the outcome of the task.

Both of these situations lead to what is popularly known as ‘micro-management’, and what I’ve referred to as ‘meddling’ above.

Managerial Meddling

Managerial meddling occurs when a manager uses her superior work knowledge to tackle a task, even after delegating it to a subordinate. For whatever reason (see above), the manager uses her superior knowledge and experience to take control of the subordinate's task instead of letting the subordinate figure it out for themselves.

This is very, very bad behaviour. We know from self-determination theory that autonomy is strongly linked to work-related happiness. Remove autonomy, and you’ll guarantee your subordinate’s unhappiness.

Worse, over time, the subordinates who stay learn that they are not supposed to take initiative, and defer the bulk of the work to the manager. Eventually the entire team's output is reduced, because the manager has become the bottleneck; worse, the subordinate never learns to act by herself. This is one of the worst examples of negative managerial leverage.

But sometimes it doesn't get to such extremes. Even if a manager doesn't delegate this horribly, it's common for new managers to feel annoyed with a new subordinate. The most common objection I've heard is “But it'll be so much faster if I do it!”

So how do we avoid this?

The first step is to recognise that delegation can only happen in a situation where both the delegator and the delegatee share a common understanding of how to accomplish the job to be done.

This common understanding not only involves technical knowledge (e.g. how to write code, or how to design UI elements in Sketch) but also institutional knowledge: things like acceptable coding practices and design standards and “that’s how we do things here” — things that remain unsaid but are adhered to by everyone in your company.

If you and your subordinate don't possess this common, shared information base, you would have to provide exacting instructions, and perform exacting quality checks — which are incredibly frustrating! The ideal scenario for delegation is that you hand off a task, not worry about it for awhile, and then come back when the task is done.

I believe most of us have an intuitive understanding of this reality. We know that a new hire should be treated differently from an experienced teammate. The latter can be a pleasure to work with: that is, if we tell the experienced subordinate to get a job done, we expect it to be done reasonably well, and we do not worry so much about the quality of the work. But a new hire is liable to mess things up, so we spend more time with her.

What is not so clear is that it is your job to make this happen quickly.

The truth is this: training is the manager's job. It is the manager's job because the manager is responsible for increasing the output of the team, and training a new hire allows you to delegate to her in the future. This also means that training and delegation are two halves of the same process.

I'll discuss training in our next chapter. For now, let’s talk about two mental hacks to make delegating easier to do.

Selfishness and the Two Hats

One hack that I use often is something I call ‘the selfish manager’: recognise that you are allowed to keep some tasks to yourself. If you are particularly interested in (or invested in) a task, it's perfectly alright to not delegate that task to a subordinate. Keep it for yourself! But be honest that you are doing this out of self-interest.

A perfect example of this is a task that involves using a hot new programming framework, or implementing a feature using a sexy technique. These sorts of tasks are very attractive to developers, and so your inner programmer might feel an intense desire to meddle in such tasks. The answer, of course: is to be explicit about your involvement. Either take it on and do it — or delegate and let it go.

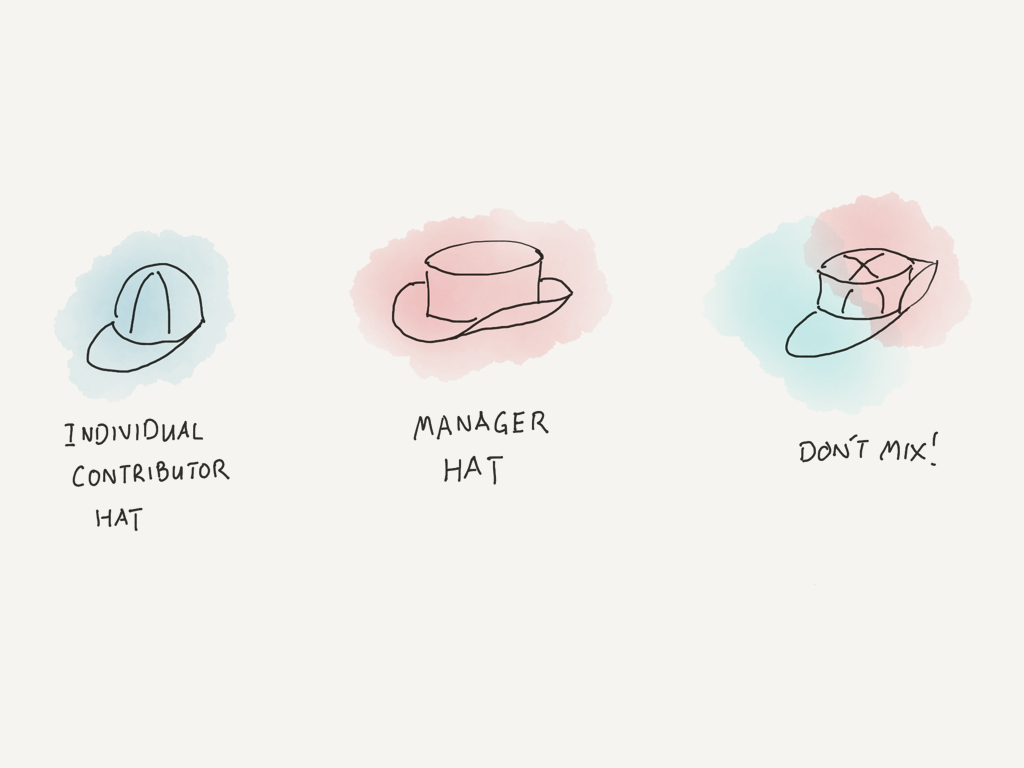

Doing so allows you to separate tasks that you want to work on as an individual contributor from the tasks that you are working as a manager. This leads us to our second mental hack: the idea of ‘having two hats’.

Most managers in small teams wear two hats: a manager hat, and an IC hat. What this looks in practice is the design team lead who is still expected to design; or the engineering team lead who is still involved in implementation. It’s tempting to say “as a manager, don’t code” but the truth is that in a startup, this is sometimes not possible.

To prevent myself from meddling, I've found it useful to always ask myself “which hat am I wearing now?” when approaching my work. The underlying idea here is that you can only wear one hat at a time.

If my current job is to perform a unit of work, then I am wearing my individual contributor hat, which means my job is to ‘get X done’. But if my current job is managerial in nature, then I am wearing my manager hat, and my job is to increase the output of the team.

The instant you have delegated a task, you must understand that you are no longer wearing your IC hat, but are wearing your manager hat instead! This means that you are no longer supposed to complete the task (which is the individual contributor's job!); your job is to increase the output of the team.

Directly meddling in a task you have already delegated is mixing your hats: you have delegated — which is managerial in nature — but you're still acting as if your job is to ‘get X done’. It isn’t! You’re wearing two hats at the same time. That looks stupid, so take one off.

Over the long term, delegating well results in higher leverage for you and higher output across your entire team, because you will be able to delegate a wider variety of tasks to a wider selection of subordinates.

Check the output

We’ve spent a lot of time talking about meddling, but let’s talk a little about checking the work of your subordinates.

First: checking is not meddling. As a manager, you should always check the output of a delegated task. Delegating without checking is abnegation — which is equally bad.

You alone are responsible for the output of your team. Even if you have delegated a task, you are still responsible for its completion as the manager. Checking is the only way you can ensure that it is accomplished at an acceptable level.

There are two ideas that you should apply here to make your job easier.

First, you should try and check at the lowest value stage of production.

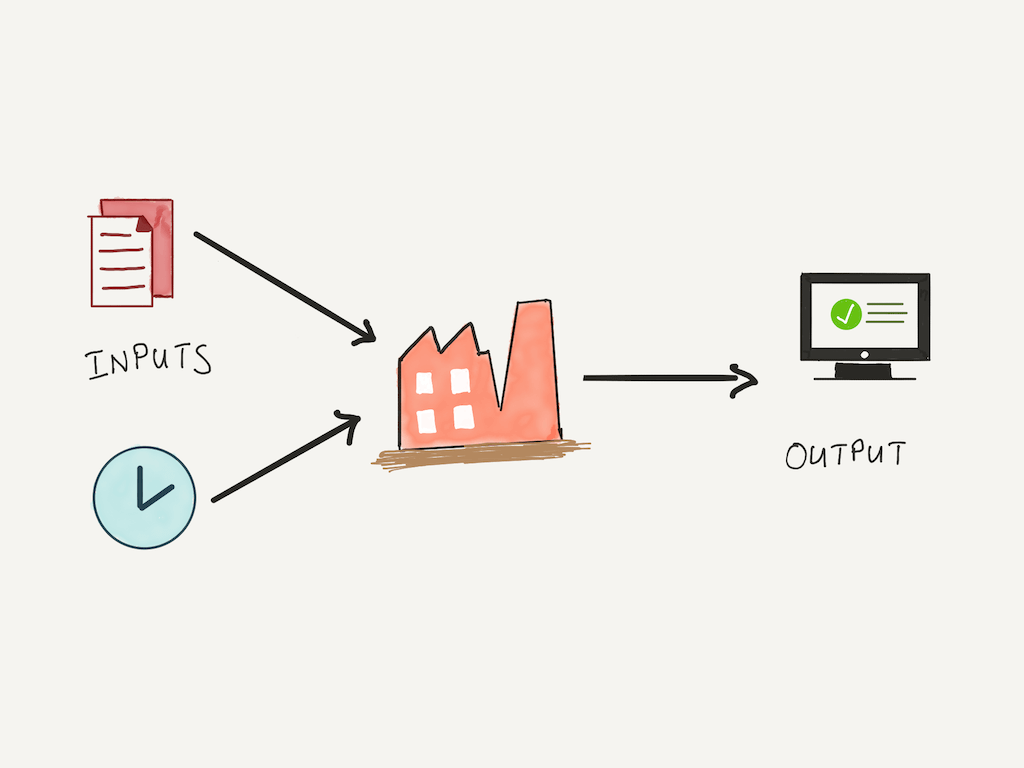

Take a moment to imagine your team as a factory. On one end, material flows in as input, and are transformed into products that are shipped out the other end as output. In a programming team, your inputs are requirements and programmer time; your outputs are a feature implementation that works correctly and solves a business need.

In a factory, correcting mistakes at the earliest stage possible is always cheaper than correcting mistakes made later in the process. Imagine how much cheaper it is for a car manufacturer to catch a supplier fault than issuing a massive product recall!

This insight also applies to your work in a startup: in a software engineering team, for instance, it is cheaper to check during the specification stage, not the implementation stage, and better to check at the implementation stage, not right before deployment.

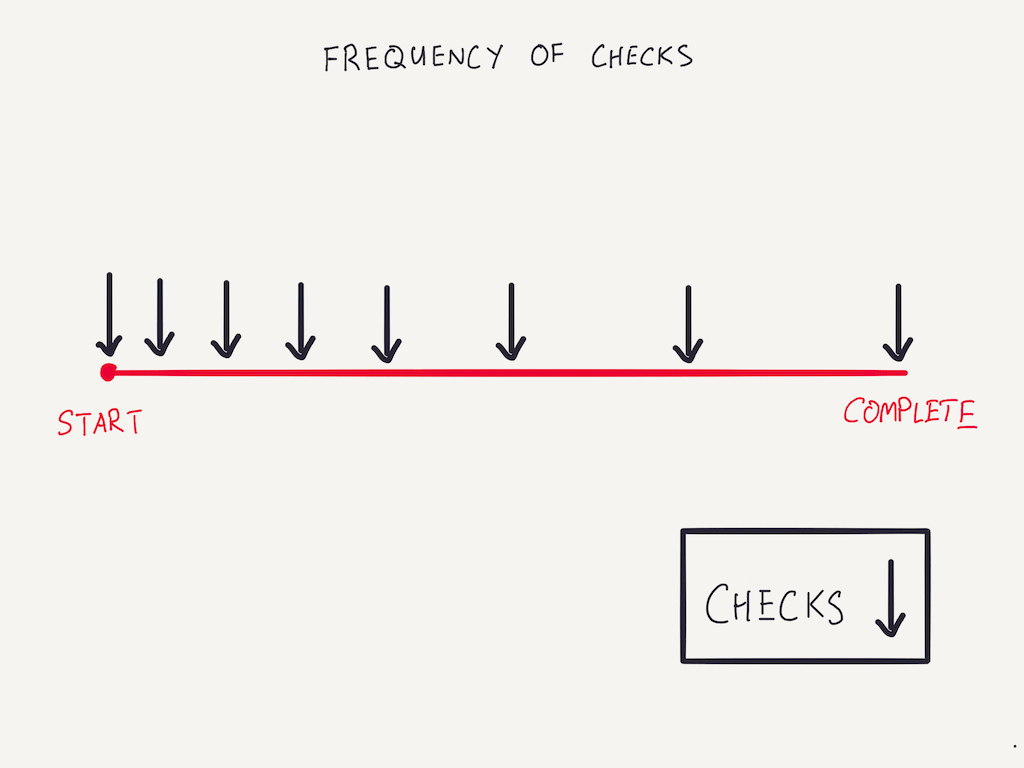

This leads us to a second insight: you should check often at the beginning, and then taper off as the feature reaches completion.

Why is this useful? Well, if you check rigorously when it is early in the process — and ensure that the task is on the right track — you free up time later to work on your own tasks. This is how a manager finds time to work on IC tasks even while handling a management workload: she arranges her delegation in such a manner so as to allow herself gaps where she doesn’t have to check as much.

That sounds fine when you’re managing a single subordinate. But what happens if you have two, or more?

This is where our second technique comes in. I’ve mentioned earlier that we know instinctively to check more when our subordinate is a new hire, and to check less when our subordinate is experienced.

But we can be more precise than that.

The secret here is to check according to your subordinate’s task relevant maturity.

For each kind of task, different subordinates would have different levels of maturity. This is more accurate than judging a subordinate as ‘experienced’ or ‘not experienced’: instead, you must judge the subordinate as ‘experienced with regard to this particular task’.

If you are assigning a task that is unfamiliar to a subordinate, then she has low TRM. This means you should check more often. The inverse is true: high TRM and you can check less. This saves you time and increases your leverage; you shouldn't be checking every subordinate equally for all tasks!

Given enough time, what happens is that you will build a sense for your subordinates’s individual strengths and weaknesses. I know to check more when assigning user interface tasks to senior engineers with bad design sense; I also free myself up and check less when delegating to junior engineers who have successfully accomplished similar tasks in the past.

This increases my managerial leverage and frees me up to do other things with my time.

What should you delegate?

If you’re a new manager, you should ideally delegate tasks that you already know how to do. This is because checking the output is easier for tasks you are already familiar with. Don’t make things too difficult for yourself: when you’re attempting to learn delegation, try and reduce the number of new things you have to learn.

What happens when you don't have a choice, though? It's a common experience to be asked to delegate a task that you yourself have no experience with.

In this scenario, you must ask for a plan from your subordinate, and check the quality of her thinking. Question her about the operational details of the plan, deep-diving at random places and asking penetrating questions until you are satisfied that she has thought through most of the considerations. Establish with her what good output looks like, and check for that output the same way you would for any other task. The general principle here is to “check the thinking, even if you can't check the process.”

Takeaways

Here are the takeaways from this chapter:

- Delegation and training are two halves of the same process.

- Training is the manager’s job.

- When delegating, use the following two mental hacks: 1) you are allowed to keep some tasks for yourself 2) you have two hats: an IC hat and a manager hat, but you may only wear one hat at a time!

- Check at the lowest value stage of production. If you check more often at the beginning, you may check less later, which gives you time to work on your own tasks.

- Check according to the task-relevant maturity of your subordinates! If a subordinate is experienced with regard to that specific task, you may check less throughout the entire process.

- When you are new to management, try and delegate only tasks that you know how to do.

- If you delegate tasks that you don’t know how to do, check your subordinate’s thinking by asking her for a plan. Then check the output against that plan.

A good manager who is able to delegate well will eventually free herself up to perform higher-value activities. But in order to do that, we’re going to need to talk about training, which is the topic for our next chapter.

Chapter 3: How to Train Without Becoming a Bottleneck →

If you're a Commoncog member, download the ebook copy of this guide here. If you're not a member, fill this out to get an ebook copy:

Originally published , last updated .