Let’s say that you’re a new manager. You’ve read The Starter Manager Guide (or some equivalent introduction to management) and you understand that the manager’s job is to increase the output of the team. You also understand that a huge part of that job is to prevent bad things from happening before they happen. This prescience — which every good manager possesses — is developed by tracking a small, curated set of information sources. Some of these information sources are quantitative leading indicators (for example: has the number of tasks finished dropped over the past month?). Other sources are qualitative ones — for example, are repeated customer complaints a leading indicator of a bigger problem?

So, operational question number one: how do you know which indicators to monitor?

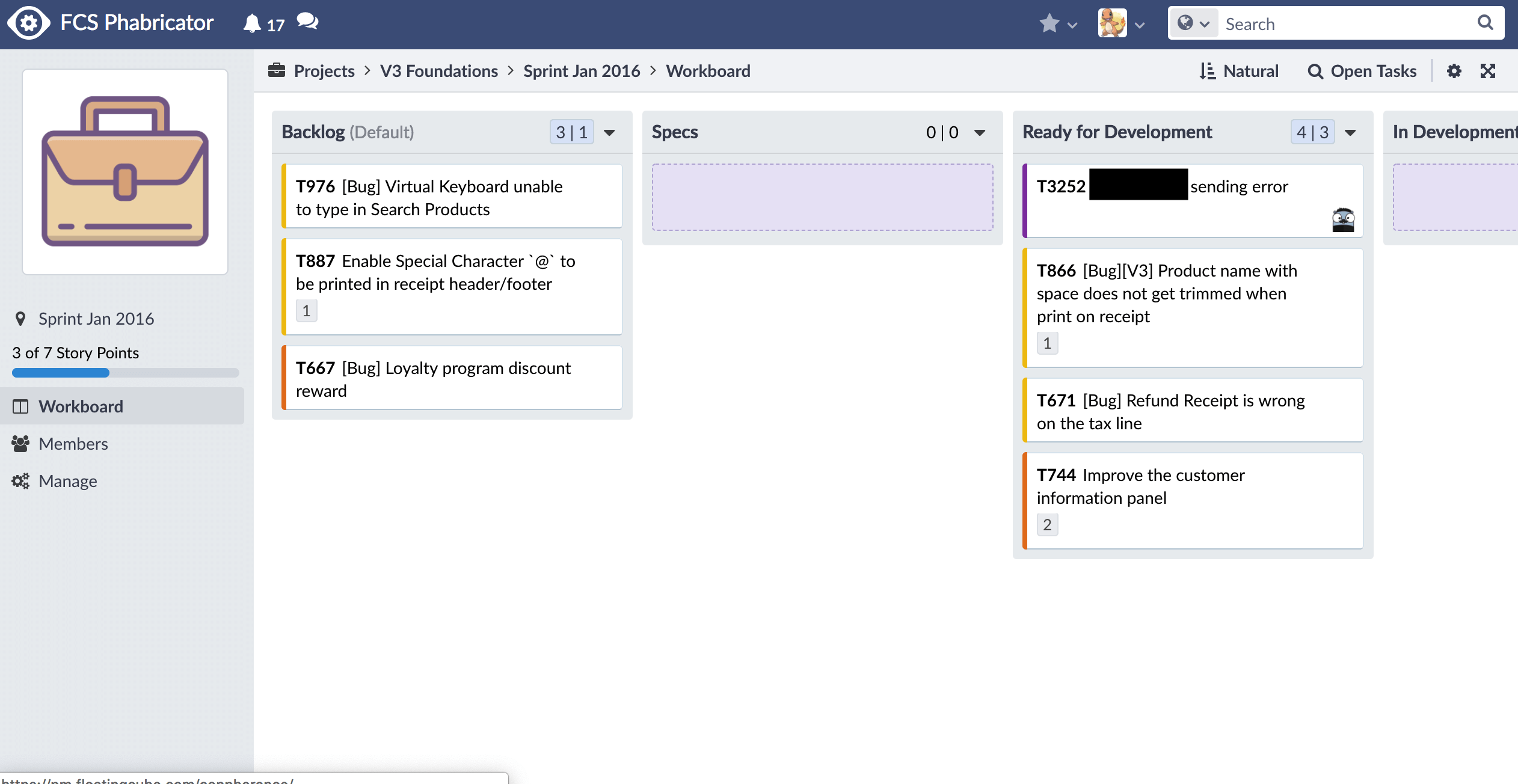

There are, of course, ‘obvious’ metrics that every manager knows to look at. For instance, most task management software comes with an overview interface, which allows you to quickly skim through your team’s current workload. If you make it a habit to check this overview interface once every week, it’s likely that you’ll have a viable source of information on your team’s workload and progress.

But there are other ways of developing ‘leading indicators’. One thing I’ve found very useful in my practice is to treat every failure or error as an opportunity to identify early warning signals.

This is a two-step process. The obvious first step is to reflect on the failure and try and identify the discrete event that indicated that something was wrong. Sometimes this event occurred on my team (e.g. an engineer stumbles upon a difficult technical problem he/she couldn't solve) but sometimes the event occured in other parts of the organisation (e.g. the customer support team deployed our devices to a client with bad WiFi; various features that depended on reliable internet connectivity broke).

The second step is to consider the information channel from which the event might be detected. Each information channel can be evaluated on the dual measures of accuracy and timeliness. So, for example: hallway gossip might be very timely but not accurate, whereas regularly scheduled project reports might be accurate but less timely. I gave an example above of the ‘overview interface’ in your task management software — but this overview might not be accurate if staffers do not update the software regularly. In my case, I could rely on my task management system because tasks were updated by a background process whenever a software engineer pushed some code changes.

I include this second step because it's not often that we consciously consider the information sources we cultivate — if we identify an event as a leading indicator of some possible failure, we tend to just do the most obvious thing to detect the event in the future (e.g. schedule more status-update meetings).

As a result of this two-step process, I began experimenting with habits that might lead to better information gathering. One example is that I began to have monthly lunches with the sales head (to dig for upcoming deals that might be thorny projects) and with the customer support head (to dig for existing but minor flaws with our software). Another was that I would spend 15 minutes every week skimming customer complaints in our CRM.

So that’s all well and good, and I believe that most competent managers would figure this out on their own. My next question is more interesting, because it is less obvious. If all competent managers build a set of early warning signals of their own, would it be possible to learn directly from them, instead of going through the long process of trial and error that I’ve just described above?

As it turns out, I believe that it is.

Copy Your Boss’s Mental Models

If your boss is a competent manager, it is highly likely that he or she would have a better mental model of your organisation than you do. This is particularly useful when you are new, because it means that you can use their knowledge to accelerate your learning.

As a simple first step, it might be useful to watch what information channels your boss pays attention to. You can either ask them (“what indicators do you watch regularly, so that you can prevent problems from happening?”) or you can just observe to see what they do.

This question may be more revealing than it appears. If your boss gives you a coherent answer, then that tells you that he or she is the kind of person who consciously watches for potential problems. But if he or she cannot answer well, then it either means that they are reactive (which, might, urm, mean that they’re not that competent), or that they’ve built up a set of information sources subconsciously (which means you need to pay close attention to what they do, and not what they say they do).

Some managers are instinctively good at cultivating information sources. This is particularly true if they came up in a very political organisation. I don’t mean to say that their information sources are formal, or quantitative, or that they even call them information sources in their heads. It could be as simple as having lunch with a certain person from a certain department once every week. Your job isn’t to start having lunch with that same person; your job is to notice what department that person is from, and to figure out why your boss is having lunch with them.

After you do, you’ll have figured out a piece of your boss’s mental model of the organisation. And you can decide if you want to cultivate information sources of your own within that department — which you might, if you believe it will help you be more effective in your job.

Takeaways

A good collection of information sources are how managers notice problems way before they happen — and act to prevent them from ever happening. This makes up one of the paradoxes of good management: if you are a good manager, your subordinates will think that you do very little. And they will think this because they won’t see all the alternate futures in which things go badly.

How do you cultivate this ability to prevent bad things from happening? In a nutshell: be conscious about your information sources, and curate a small collection with different levels of timeliness and accuracy. These sources may be quantitative (number of code commits per week) or qualitative (a lunch with the sales lead every fortnight). They may be constructed from trial and error, or from watching other competent managers in your organisation.

The secret here is that information sources often correspond to ... well, political factions is one way to put it, though not every startup is political. The other way to describe this is that your boss's information channels often indicate 'organisational dependencies' — like for instance, my dependency on sales in my previous company. Either way you look at it, you now have the tools to notice these channels when others do not. God speed and good luck.